‘The Organized Mind’ Book Review

Francesco Marcatto24 Apr 17

I love waiting at airports. I use the time to browse the book shops looking for new treasures. Last time, browsing the shelves at Stansted, I stumbled upon a book called ‘The Organized Mind: Thinking Straight in the Age of Information Overload’.

I was immediately attracted to it, but my bullshit meter was beeping dangerously. I tend to be very skeptical of pop-psychology books, which are too frequently only useful to keep the doors open when there is a drought...there are many notable exceptions of course, but I was wary!

Thankfully, the author turned out to be a respectable researcher and professor of behavioral neuroscience, and the book is an unexpected little gem. In slightly less than 400 pages, Daniel Levitin brings us through the recent advances in the science of memory and attention and shares with us some advice on how to manage and survive the everyday assault of information.

We bring it on ourselves!

A key point for me was the idea that yes, we humans living in the modern age are exposed to an overload of information, but we also make it worse than it has to be, for two main reasons:

-

We believe that more information is always better to make a reasoned decision;

-

We think that we can do multiple things at once.

Frantically jumping from one thing to another is not the right way to be productive in the information age!

Psychology and cognitive neuroscience agree this is not how our minds work, and our mistakes beliefs lead to stress, procrastination, and bad decisions.

Multitasking

The first nemesis in the book is multitasking. We think we can do two or more things at the same time, and do all of them well. In reality, we are switching from one to another very quickly, and this is cognitively very costly. Levitin’s metaphor is illuminating: we feel like we are keeping a lot of balls in the air like an expert juggler, while in reality, we are ‘more like a bad amateur plate spinner, frantically switching from one task to another, ignoring the one that is not right in front of us but worried it will come crashing down any minute.’

Information overload

The second arch-villain is information overload. More information is not always better. We are information hungry because we think we need every little chunk of it to make the best decision. And indeed, too little information is no good, but perhaps surprisingly, so is too much. There is a limited amount of information we can process in any given period of time, and when we exceed the optimal amount, we enter into information overload, causing a decline in performances. The bad news is: the optimal threshold is quite low.

Consider the example of buying a new house. We can all agree that the smart way to do it is to compare many alternatives (i.e., different houses) on a lot of attributes (characteristics such as location, the number of rooms, price, etc.). However, the maximum number of the parameter we can realistically process is about ten. This means that you can compare, for example, two houses on ten attributes, or ten houses on two attributes. Of course, you can try to keep track of more information, but it will likely lead to poorer choices. If you think that ten pieces of information are not that bad, remember that it is a generous estimate (‘the maximum we can process’), and the optimal number is close to a more modest five.

Things we can do

Ok, so if multitasking is an illusion and even small amounts of information could be too much, what can we do to improve our stressed lives?

The main takeaway points from the book are structure information, learn to prioritize, learn to delegate and just let some things go.

Structure

Giving order and structure to just about everything in your life, from the files on your computer to the kitchen tools, keep us from forgetting or losing things and make us work smoother and with fewer frustrations. Less ‘honey, where my car keys are?’ moments. You don’t need to have a place for everything, it’s fine and useful to have a place for all these things that are hard to categorize, such as a ‘misc’ folder in your documents or the common ‘junk drawer’, in my case on the sideboard of the dining room.

There is more than common wisdom behind this suggestion, Levitin traces it back to Shannon’s information theory and Kolmogorov’s complexity theory. The more structured a system is, the less complex it is. And the less complex a system is, the more at ease we are with it in our everyday lives.

Prioritize

The other big suggestion is to learn to prioritize. The decision-making network in our brain doesn’t prioritize, says Levitin, and we are only able to make a certain number of decisions per day. Once we reach that limit, our ability to make good decisions is reduced drastically, no matter how important they are. So, instead of trying to do everything, we should learn to separate the trivial from the important and focus on the latter only.

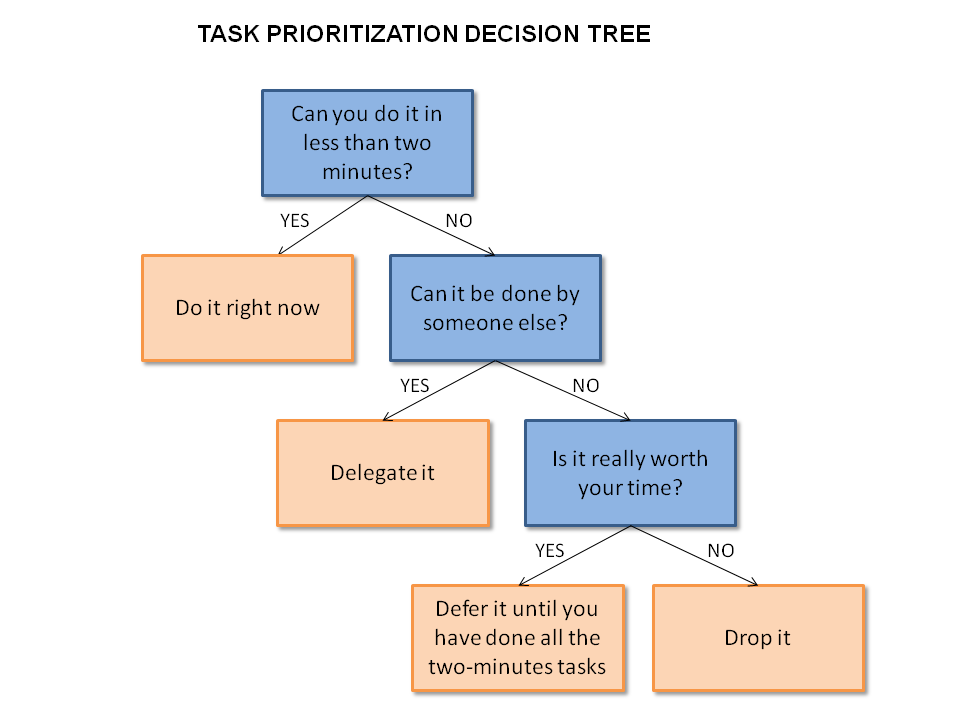

A good heuristic for prioritizing our tasks, borrowed from the efficiency expert David Allen, is to categorize them as follows:

- Do it;

- Delegate it;

- Defer it;

- Drop it.

And if something can be done in less than two minutes, just do it right now (two-minutes rule).

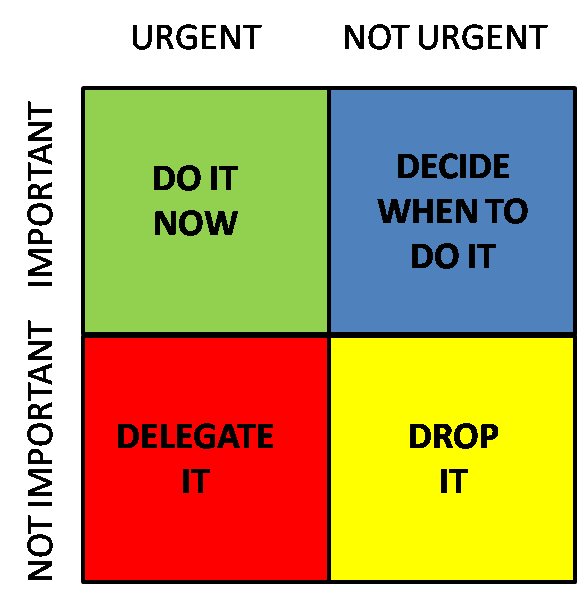

This suggestion reminds me a lot of the so-called ‘Eisenhower Matrix’, a decision principle to evaluate what it’s worth doing using two dimensions: important/not important and urgent/not urgent. Both systems say roughly the same: concentrate on the important, and learn to delegate or just drop the rest. Your productivity and sanity of mind will appreciate it!

These suggestions are smart and easy to understand. The problem is, they rely a lot on willpower, it’s likely that you’ll have to change your usual way of doing things in order to apply them. But it’s fun to practice!

A final comment

Overall, ‘The organized mind’ is a great book, insightful and well written. Some sections about the neurochemistry of our brain are a little boring, I prefer behavioral-level explanations over neural-level ones, but Levitin managed to keep the neuro-jargon at a minimum. If this article has piqued your interest, I’d thoroughly recommend the read. If you are interested to read more about productivity and information overload, I wrote another article on this topic: Team communication vs. distraction.