Random stimulation and associative thinking

Francesco Marcatto27 Apr 16

Creativity and associative thinking

The creative process can be viewed as an associative process, that is, a process consisting in creating new associations between previously unconnected ideas. In other words, creativity is like connecting the dots.

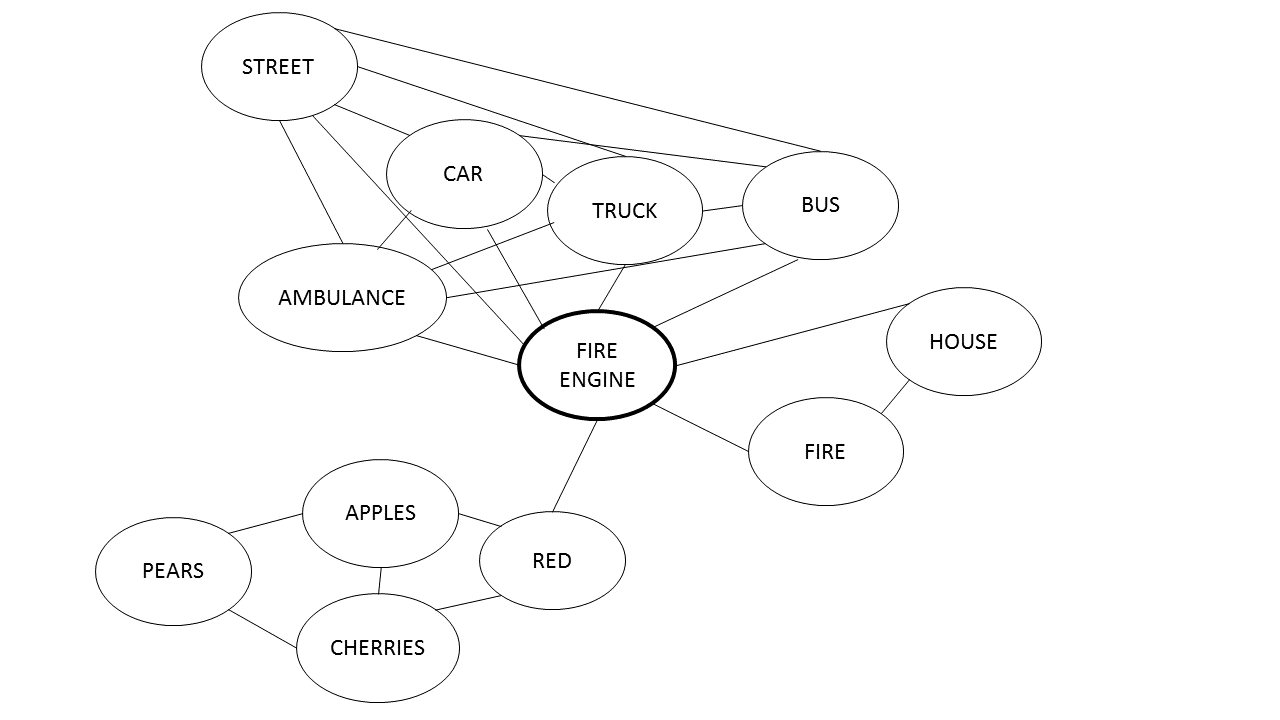

Current cognitive psychology models of memory view human memory as an associative network (Collins & Loftus, 1975). Ideas are stored in nodes, which are connected by links of meanings (semantic network). When a node is activated, the activation spreads out to other nodes linked to the original source. Activation decays as it propagates through the network, so that related concepts, which are closer to the original node, receive more activation than less related concepts. As you can see in Figure 1, the various vehicles are closely related, so when the concept 'fire engine' is activated, activation spreads to the near nodes, so that they are more quickly associated and retrieved from memory. Conversely, less related nodes will receive few to no activation, so the concepts will not be retrieved.

Figure 1. Example of a semantic network (adapted from Collins & Loftus, 1975)

Figure 1. Example of a semantic network (adapted from Collins & Loftus, 1975)

This spreading activation mechanism is at the base of associative thinking, that is the process of retrieving information from our knowledge and automatically find patterns across elements. As you can easily understand, standard associative thinking will generate more often associations between concepts that are strongly related. In other words, most associations are like cat – dog or car – tire, so very ordinary and far from being creative. But if we can prime many divergent associative pathways, one of these may eventually lead to the key concept that helps in solving the problem or creating something that is both novel and useful (Martindale, 1995; Simonton, 2003).

Cues for activating new pathways can derive both from internal mental events (e.g., other thoughts) and from external events in the outside world. There is little we can do about other internal mental events, but we can find methods to provide various kinds of information for stimulating new original associations. The most commonly adopted methods for encourage users produce unusual associations of ideas come from the family of random stimulation techniques. All these techniques consist in presenting the user with a random stimulus, in form of a word, an image, a newspaper headline, a website etc.

Our mind is very good at making connections, and will do it no matter how far two concepts are from each other. Random stimulation is important, as the unpredictability of this new input will lead to explore new associations that would not emerge automatically, and hopefully trigger novel ideas. So, the randomly selected stimulus force you to look at the problem from a different, unconventional angle, and increase the likelihood of coming up with a brilliant 'Aha!' experience of insight (Weisberg, 2015), and produce more creative ideas (Finke, Ward, & Smith, 1992).

The random word technique

The most popular technique for exploiting the power of random stimulation is the random word technique. In its basic form, this technique is very easy 5-steps process:

- Start by stating clearly the problem: what it is that you want to generate new ideas about? You might need to come up with solutions to a problem (such as increasing sales), or ideas for a new product, or maybe you just need direction. A good strategy to write your problem, is to write it as a question, for example “How to increase e-commerce sales?”

- Pick up a random word. Don’t take the first word that comes to your mind, or you will likely explore already existent associations (this is not psychoanalysis, the aim here is to create new associations!). Use instead a real random method, for example close your eyes, flip through a dictionary and place your finger on a page at random. The word closest to your finger is your random stimulus, take it and write it down even if you don’t like it! Other possibilities are to use tools and apps for generating random words.

- Look at the random word: what does it makes you think of? Take some time to write down any associations that come into your mind when thinking at the random word: you can write other associated words, but also short sentences about the feelings, past experiences, memories and other things about which the word reminds you.

- Now that you have activated many different concepts, go back to the original problem. Can you find a pathway linking the new associations with your original problems? The linkage can be vague and tenuous, and you can also use metaphors and analogies. Don’t be afraid if most connections don’t seem fruitful: in idea generation quantity breeds quality, it takes a lot of attempts to find the right idea. Remember to write down and store all ideas, even the most strange and illogical, at this stage most ideas are like seeds that need care and consideration to grow into beautiful plants.

- Look at the ideas you have wrote down: is there anything brilliant, or with the potential to solve your problem? If no, pick up a different random word and start the process again. Even if you have found a good solution, try the process again with other words, it is always useful to have more solutions at hand.

So, this is the random word technique, easy and powerful. Anyway, be aware that it isn’t guaranteed to always solve your problems or deliver novel great ideas. Indeed, the odds of chancing upon the most fruitful associative sequence is quite unpredictable: sometimes the correct association arrives early, sometimes a bit later, and yet other times even later still (Simonton, 2003). Our final advice is to relax and be patient, don’t worry if the first attempts don’t produce great results. As with other random stimulation techniques, practice regularly until forming unconventional connections becomes a beautiful habit.

References

- Collins, A. M., & Loftus, E. F. (1975). A spreading-activation theory of semantic processing. Psychological review, 82(6), 407.

- Finke, R. A., Ward, T. B., & Smith, S. M. (1992). Creative cognition: Theory, research, applications. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Martindale, C. (1995). Creativity and connectionism. The creative cognition approach, 249-268.

- Simonton, D. K. (2003). Scientific creativity as constrained stochastic behavior: the integration of product, person, and process perspectives. Psychological bulletin, 129(4), 475.

- Weisberg, R. W. (2015). Toward an integrated theory of insight in problem solving. Thinking & Reasoning, 21(1), 5-39.